Dr. Corinne Vinopol and her Legacy

By Carol Colmenares

Corinne warmly greets us from her study room, with her loyal companion Jackson, a Jack Russell Terrier, by her side. The impressive shelves that serve as her backdrop are filled with books and other materials, showcasing her vast knowledge and experience in various fields. It's clear that Corinne is an intelligent and well-read individual, and it's an honor to have the opportunity to chat with her in her cozy and welcoming space. She describes herself as a very old person, but her energy and enthusiasm in describing the projects she passionately takes on can easily fool a twenty-year-old. Corinne grew up in Baltimore, Maryland, and came from a family with two parents, a grandmother, and two siblings… “and a dog, always a dog.” Just before World War I, both sets of grandparents had migrated from what is now Poland. Like many immigrants searching for a better life, their experiences have helped shape the country and its rich cultural heritage.

“I grew up in a pretty poor family and did not have a lot of educational guidance for higher education, and I wanted to go to college, and I wanted to become a reading specialist.”

Luck, or default as she calls it, would take her to a highly regarded, all-girls public high school. The same one her mother had attended. The education she received there laid the foundation for her to pursue higher education and opened up many opportunities. Corinne fondly remembers her time in high school. At the time, women were starting to have equal rights and possibilities. She was in an accelerated program with select girls from all over the city. The program was competitive but provided the best education and teachers. Corinne made lifelong friends and was prepared for college and life.

“If you went to a co-ed high school, back in those days, women were never president of the senior class. They weren't head of the yearbook or anything. In our school, we had to do everything. So I think that developed a lot of moxie in all of us, and a lot of the women became very successful.”

After graduating with several honors classes and qualifying for advanced credits in college, Corinne put herself through undergraduate school with the help of scholarships and finished in 3 years. Her love of literature, reading, and writing led her to major in English, where she met her mentor. It was in one of his classes, while giving a lecture on dyslexia, that he told her he was starting a program in deaf education and wanted Corinne to be in it.

“I said, no, I don't know any deaf people, and he said, well, I know that you are ahead of where you're supposed to be credit-wise, so you should have some flexibility to take a couple of courses… if you do that, and you like it, I'll get you a scholarship for the summer.”

Her love of learning and the opportunity to remain at school would take Corinne on an academic path, finishing her undergraduate, her two master's, and ultimately her doctorate.

“I was very lucky to get a mentor, Dr. McCay Vernon, when I was an undergraduate, and he kept pushing me through until I got my doctorate.”

“I started my career as the first teacher of multiple disabled deaf children for Baltimore City public schools and later went on to Maryland School for the Blind. Way back in those days, the multiple disabled deaf children did not go to the school for the deaf.”

Corinne's first job was in Baltimore City at a program for children with cognitive disabilities, working with a group of deaf students whose secondary disabilities were considered too difficult to be handled by other deaf education programs. The principal was told to find her own building, and she found one at the foot of Broadway, which was a very rundown area at that time.

“But back in those days, it was where the sailors would come and drink and meet prostitutes. And the building was 150 years old and had been condemned before we got there. They reopened it just for us.”

Eager and young, Corinne decorated her room in the old building with posters, stickers, and colorful designs. She found herself over her head when eight children with multiple disabilities, including emotional trauma, arrived in her classroom. Many of the children with whom she worked were disabled in utero from the rubella epidemic of '64 and '65.

“There was nothing in my education that had prepared me for this. Almost none of them had any language, and they were totally out of control; I had one child faking seizures, another one who was trying to self-injure, a child who was deafblind, and aggressive, a little kid who was hyper and hard of hearing, one child had been locked in a closet for nine years, and oh, this was also during the rubella epidemic, so I had the kids from the rubella epidemic."

Despite the challenges, Corinne persevered and managed to get her students to focus. She removed all the decorations and instead set up chairs in the front with little plastic bags in each seat. She then brought in candy, “and if the child even gave me one second of eye contact, I showed the candy. I pointed at them, I pointed at the bag, put it in the bag”.Within 30–40 minutes, she had everyone in a chair. This experience challenged her, but also showed her that she loved the children and loved teaching.

“People say, you're very patient. I'm like, no, I'm very stubborn.”

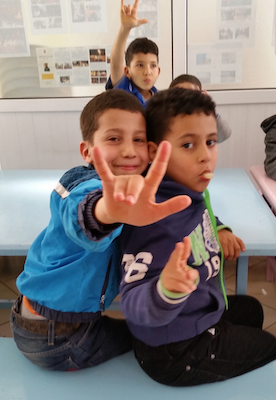

In Morocco, Corinne would reminisce about this early experience years later when she spearheaded a small project funded by USAID and implemented by her company, the Institute for Disabilities Research and Training, Inc. - IDRT.

“If somebody had asked me, you know, if I thought in my late sixties I was going to be, uh, heading up an international program right when I was on the cusp of retiring, you know, I would've said no.”

The most rewarding experience for Corinne was working directly with children and the staff in Morocco on an international program, which led to a lot of success and personal fulfillment. The project started small but quickly grew as they kept asking for more resources. This led to awards at both the White House and the United Nations. Corinne and her team found that only 15% of deaf children attended school, and most of their education was provided by associations of the deaf. There was little education past the sixth grade.

The most rewarding experience for Corinne was working directly with children and the staff in Morocco on an international program, which led to a lot of success and personal fulfillment. The project started small but quickly grew as they kept asking for more resources. This led to awards at both the White House and the United Nations. Corinne and her team found that only 15% of deaf children attended school, and most of their education was provided by associations of the deaf. There was little education past the sixth grade.

“My philosophy was to work both from the ground up and the top down, to let people know what their capabilities are, but also to influence people in power, the policymakers.”

After much dialogue and pushback, the policy changed, and deaf children were allowed to attend school all the way through. They also developed an assessment for early-grade reading and sign language. The team documented over 3000 signs in Moroccan sign language, surpassing previous attempts, which only had 200 to 500 signs documented. They introduced the use of computers and software into the education of the deaf in Morocco, replacing the use of chalkboards. They set up instruction on various subjects such as special education processes, language development, and deaf culture. As a result of their work, a teacher training program was started in Morocco, as there was no special education teacher training at that time. They left behind materials, training, and software, which continued to be used and also initiated ongoing research.

“It was a lifetime opportunity and life-changing. I'm still in constant communication with people over there.”

“It's very gratifying to be able to leave a legacy like this.”

Corinne, who is on an advisory board for an impact center that helps bring assistive technology to market, shares her thoughts on developing technology for people with disabilities.

“It's an iterative process. It always has to come from the user. It's not from the developer. I can have an idea, but in the abstract, it means nothing. It only means something if the people who are going to use it can use it, value it, and it makes a change in their lives. So that's where you need to start.”

As an advisor to Dicapta’s project Enhanced Access to Video for Students with Sensory Disabilities through Emerging Technology - EnhAccess, Corinne once again surprises and delights us. Her interest in the Spanish-speaking community stems from her own experience as a foster parent to several Latino/Latina children. Her last foster child is still considered a part of her family and is from Peru.

Corinne on Dicapta: “I'm totally inspired, by the efforts, by the dedication. I'm just enthralled when I hear about the awards that you all get, but mostly it's just such a dedicated group of people.”

“It's not only the quality of what you do, but the dedication to the people that you're serving. Your heart's in a good place. I think that sets you apart from many other groups who may aspire to be in the business.”

Corinne Vinopol has taken on several roles throughout her career, including special education teacher, principal, software entrepreneur, teacher trainer, developer, and hearing officer in special education disputes. Each role has presented its own challenges and rewards, and Corinne has left a part of herself and a lasting impact on each one. And just like Corinne can’t choose a favorite book, we can’t choose a favorite story. In a way, each story leaves us with a bit more wisdom, inspiration, and enlightenment.